The Venus on the Rhone River Learn how a ZBrush team member created a reconstruction of an ancient statue found in France.

ZBrush in Historical Reconstruction

This is a making-of article showing a reconstruction made by Pixologic French team member Thomas Roussel. The project was of a Venus head found deep in the Rhone River, in Arles, a city located in France and famous for its old Roman elements. Since the statue's discovery, the Arles museum has performed much research into its original appearance, from the missing parts to the coloration. Additionally, this project has been documented for a TV broadcast aired on a prime time TV show on French national television, showing elements of ZBrush to more than 3.6 million viewers!

Discover how ZBrush was used to work on the scan data of the head, rebuild the figure and finally paint it, in collaboration with the Arles museum and Eclectic Production / 2ASM.

Introduction by Thomas Roussel

I became involved in this project after some interesting discussions at the Japan Expo 2010 tradeshow with François Arnoul, the French distributor of ZCorp 3D printers and scanners. He had to scan an old Venus head requested by the Arles Museum for analyzing, and they were looking for someone to try and reconstruct the missing parts of the head and recreate the painting. The statue was missing nose, lips, chin, eyebrows, parts of the eyes, hair and forehead. Some color pigments had also been discovered, which was surprising for a head which has been under water for such a long time.

This project was exciting because it was far from the "usual" VFX, video games or illustration use of ZBrush and mainly pure sculpting, including a lot of constraints. The model had its existing shape and when reconstructing the missing parts I had to take care to not go in the wrong direction. I couldn't go too far into the wild creatively; it's a reconstruction, after all! But doing this allowed the museum to try out a number of hypotheses without touching the original Venus statue.

Project Strategy

As I mentioned above, the strategy to work on a 3D scan is a little bit different from traditional creative sculpting. It's not a creative work and it is crucial to rebuild Venus as it was in the past. To accomplish this, I chose to through the following steps:

Cleaning the 3D scan.

Roughly sculpting the missing parts on a 3D layer.

Adding extra parts like hair braid, neck and shoulders to give a better overall look.

Doing a full retopology after the previous steps were done. This allowed me to work more easily with multiple levels of subdivision and also remove some small artifacts in the topology.

Refining the sculpt.

Using PolyPaint to create the color based on research done at the museum.

Final refinements and model presentation.

While defining this strategy and doing the first tests, I couldn't see the original head. I had to talk with the museum about the references and validate some steps by phone. I only had access to photos as references, based from another Venus which is in the Louvre museum reserves.

On top of that, I also had to record the entire sculpting process for the TV broadcast, which I was afraid would not be very helpful for my computer's performance! Thanks to ZBrush, I didn't feel any slow down at all.

3D Scan Cleaning and Beginning the Sculpting Process

Once the 3D scan was imported into ZBrush, I had a mesh of 1.5 million triangles. That's certainly a good amount of polygons, but not something most ZBrush artists would even blink at. The challenge here was that these were simply raw triangles rather than subdivision levels, which means potential slow down. Fortunately, it wasn't an issue at all on my computer and everything ran smoothly from navigation to sculpting. The problem wasn't polygon counts at all...

The real problem was that the triangulated surfaces created by 3D scanners are not very friendly with subdivision surface software like ZBrush when trying to divide the polygons to add more geometry. On top of that there is a stair-stepped layer effect on the scan surface which had to be removed. The first step was therefore to smooth this effect without losing any important details. There are no secrets to accomplishing this. It was mainly patient use of the Smooth brushes and occasionally the Clay brush to fix small scan errors.

Once this step is finished, I begin to build the missing parts. For this I still used the Clay brush and sometimes the Claybuildup brush. In this way I added the nose, lips, chin, eyebrows, parts of the eyes and hair.

Adding to the complexity was that it is typical to work symmetrically when sculpting a digital figure and then add asymmetry at the end. For example, it is a lot easier to sculpt a nose in symmetry and then apply deformation or a pose when done. That was not possible with this project, which was a model that had already been posed two thousand years before I got to work on it and so was asymmetrical from the start. I had to take great care with this specific point, which hounded me through all the reconstruction steps. This was in fact very good motivation. It reminded me of my clay sculpting training: No undos, no 3D layers and no symmetry!

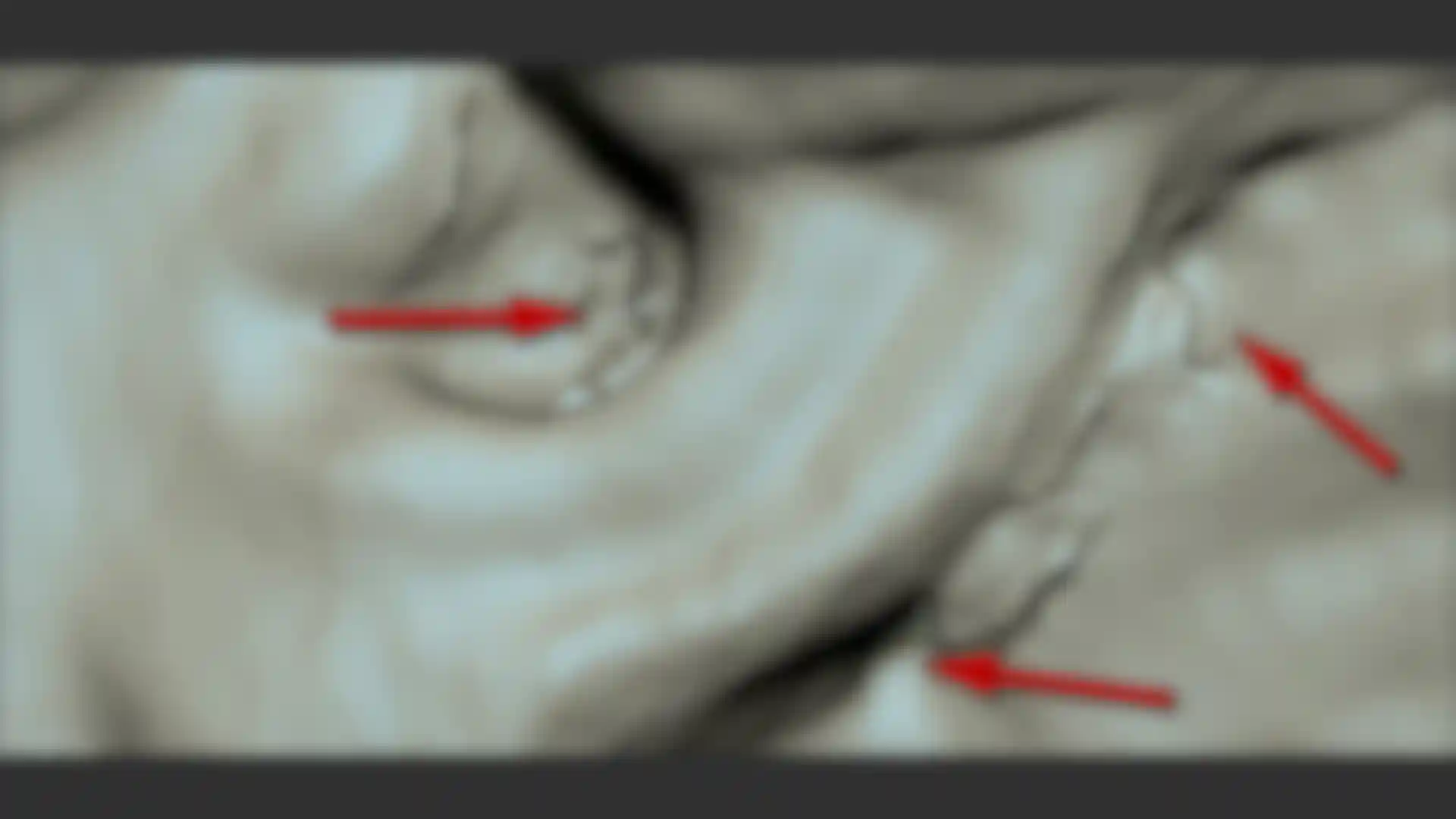

Speaking of layers, I used them for almost all stages, which allowed me to toggle with a single click between the original mesh and my sculpt. It was invaluable for comparing my sculpting to the original to ensure that I stayed true to the source. I also used ZBrush's TimeLine feature, where I stored key frames for each layer at value 0 or 1 which I could then move between. These ZBrush features were very important as I had to regularly check in with the Museum to see if the progress was in a good direction or not.

It was very easy to go further than I should have, but on the other hand these features were also a good solution to explain some of my choices. I remember perfectly a discussion with Pascale (the museum curator) as she wanted me to refine the nose and have it thinner because what I did was too large in her opinion. I sent her a couple screenshots showing her that I was respecting the marks visible on the statue where the original nose was, and how my sculpt started exactly at these marks. This Venus, as I mentioned earlier, is not as thin as our reference and has more fat. It is important to respect this kind of information while sculpting, even if it's easier to say than do!

From a technical standpoint, these last steps were not very hard to do. I was mainly sculpting with the Clay, Move and Standard brushes, combined with masks. I only had to take care to produce a natural look while still respecting the reference.

Adding the Missing Parts

Like I mentioned in the introduction, it was decided to add some missing parts 'around' the existing head in order to provide a better visual effect and feeling of the Venus. This required neck, shoulders and hair braids while respecting the reference Venus. Regarding the braids, the existing hairs and some parts of the neck have marks on them which confirm the hypothesis that braids originally existed at these locations.

To do this part of the project, I added several ZSpheres as SubTools which I put approximately where I needed them to be. I then refined the position of each piece before converting the ZSpheres to fresh polygons through Adaptive skinning. With the hair braids, I tried to put these ZSpheres as close as possible to the reference. For the neck and shoulders, it was more roughed out, since the purpose was only to have some base material to sculpt with. I then began to sculpt and move the new polygons about as needed before going to the next stage.

Retopology and Projection

The TV broadcast required that I be able to show a transition from details of the original 3D scan to the finished model. To accomplish this I did a bit of a magic trick with layers. After retopology, I projected the original model onto my new 3D mesh. I then created a new layer and did a second projection using the final model. I also did some various editing between these two stages through morph targets and the Morph brush, allowing me to correct minor artifacts caused here and there by the projection (especially on joint areas).

To be honest, these steps are all very technical and not very artist-friendly. But at the end, having a retopolgized model brings a lot of benefits as it lets you work with multiple levels of subdivision. This provides a better sculpting feeling, lets you more easily refine the global shape if needed without losing the top details and more. You might also notice that the topology is quite uniform and constant. Each polygon is as square as possible and the size is close to be the same everywhere. Thanks to this, I was able to have the same density of details across the entire mesh and I didn't need to add more subdivision levels to certain areas because they lacked polygon density.

Final Sculpting Steps

Now came time for all the small details and refinements, which was also the longest part. As usual, blocking the mass can be very quick and sculpting the small details can be very long! At this point it became a matter of decisions like, "The nose needs to be more in straight line," "the hairs must be less smooth and should have a scratch effect on the surface," etc. Every change was done on 3D layers, which allowed me to check as often as necessary to ensure that everything was fine without the risk of breaking something. This also provides us with the ability to test things we wanted to try, which was a great freedom for the research parts of the project.

Painting

It now came time to meet Pascale from the museum in real life, as well as Brigitte -- a great specialist in research on the coloring of old statues and in polychromy. She spent some time analyzing to find the colors of these old pigments, but the more she found, the more some of our hypotheses would fall apart. As an example, black pigments on the statue proved not to be color at all but were in fact carbon. That's how we learned that this Venus had been in contact with fire at some point in her history!

Pascale's job now began, including all these new constraints. She had to figure out all over again how to paint this Venus as what we'd learned didn't match our original assumptions! The first pass was to create black marks on specific areas as was usual on old sculptures, like the border between the skin and hairline, the corner of the nose, the eyes and some areas of the lips. Later, we worked on the hairs and tried to find the best corresponding color, added some dark areas in the hairs cavities and also cheated the specular on the tops of the hairs. At a later stage, we focused on the eyes and lips.

To explain the technical aspect of this process, all the PolyPainting was done on layers just as had been done with the sculpting. This lets us paint areas without affecting underlying layers or erase other areas when needed. The brush used for this was mainly the Standard brush with various modified alphas, sometimes mixed with Lazy Mouse and Stroke variations. We always worked at a very low RGB Intensity.

Because of timing issues, I had to finish the color painting later. But to be honest, I'm not a big fan of the color even if the museum was very happy with the result. (Yes, that is what was most important, but I'm a perfectionist!) It has been very hard to choose the colors and style as recreating something from 2000 years ago has too much that's simply unknown. This is partly because most of the previously founded statues have been scratched, partially destroyed or otherwise altered by the research done on them over time. Many have also had plaster molds created of them from which to produce copies – a process that severely damaged the original paint job. I have in fact been told that we don't have a way to know anymore how these statues were colored. We can only hope to one day find new statues with more color pigment visible on them.

Preparation of the 3D Print

An extra stage was to create a model ready to be printed as a real-world object. For this I created the UVs with the help of UV Master. They were done with a single click as I didn't have need for fully optimized maps.

The next step was mesh optimization with Decimation Master to reduce the polygon count to approximately 300,000 triangles which was enough for a quality print. Finally, I used 3D Print Exporter to create a VRML file including the texture and scaling information.

I know that the Printing company will hollow the model to reduce its total volume, reducing the printing cost. I didn't manage this step.

The Last Word

I came into this project with a lot of unknowns. In the end, I learned a lot about this field from the enthusiasts and specialists I had the privilege of working with, which has been a good booster. ZBrush was a great help, allowing us to do as much testing and research as was needed without a glitch -- even on some complex steps like mixing layers and detail projections.

Now it's time to wait for the 3D printed version!