Monitoring Spectre How Vincent London used Cinema 4D to deliver a host of displays and infographics for the latest Bond movie.

It wasn't that long ago that in the world of espionage that the choice of computer operating system was easy: the bad guys used Windows, the good guys used Mac OS. But these days, no self-respecting covert operation or crime syndicate would settle for off-the-shelf software. Such is the case with the latest James Bond movie, Spectre, which required more than 300 animations across 23 scenes.

The task of creating the infographics and cutting-edge user interfaces fell to Vincent London, specifically creative director John Hill, who co-founded the studio alongside creative director Rheea Aranha. Hill was approached by London VFX house Rushes to head the project and to creatively direct and design the work.

Working with director Sam Mendes, Hill led a team of around 26 over the course of the thirteen-month project, from pre-production through to the film's release. "We created over an hour's worth of animation in total at mainly 1080p resolution," he says.

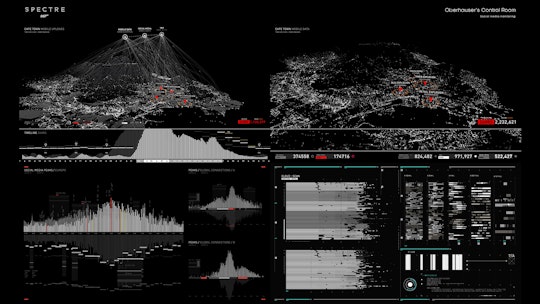

“One of the largest sets to populate with graphics was Oberhauser's Lair with more than 120 monitors. I designed the graphics so they could be arranged in rows to complement the long corridors and lines of workstations.”

"Much of our work had to be designed and tested before shooting to ensure the graphics would not only compliment the set designs and camera setups but also work as fully interactive props," he adds. "Some animations required full live interactivity with the actors for key storytelling, and we tested these prior to shooting so I knew they would do their job in camera. It's a bit of an art form getting these animations right and requires a fair amount of experience to translate a piece of script into a very important storytelling device that has to work in a changing live scenario."

The screens in Spectre feature a combination of 3D and motion graphics-style imagery, but around 90% of it was created in Cinema 4D, with After Effects used for some 2D animation and compositing. "We used Cinema 4D for many graph animations as they're quicker to create using MoGraph than in After Effects – especially when working within the modular framework we designed for Q's branch and the freeform graphic language of Oberhauser's Lair."

Hill and his team used the Hair and MoGraph systems inside Cinema 4D and utilized Insydium's X-Particles to create data clouds and other particle-based animations. TurbulenceFD from Jawset Visual Computing also makes an appearance.

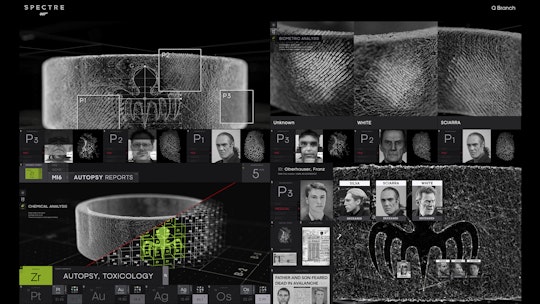

One background image shows material analysis, viewed at nanoscale levels, represented in a pin-art style. "This was made using Hair," comments Hill. "It's the only way to create such a huge amount of objects without grinding your machine to a halt. Hair works very well for this type of work and allows you to create some lovely complex designs."

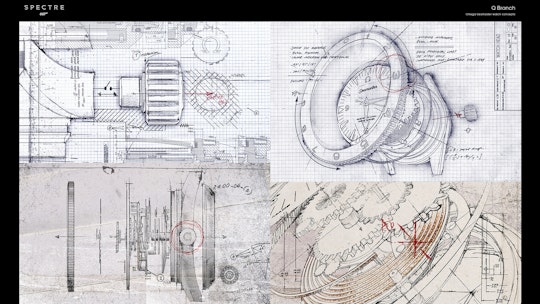

Hill also comments that developing ideas for the Omega Seamaster 300 watch schematic breakdown was particularly enjoyable.

The Spectre ring analysis displays the results as a series of elemental building blocks. "We modeled the ring in various styles," says Hill. "Electron microscope, photoreal, gamma, spectrometer… again for flexibility in the main composite. MoGraph was used to create the voxel grid system for isolating the chemical constituents of the ring."

"I designed and modelled the Earth in Cinema 4D for the satellite tracking screen," says Hill, "again making use of the 3D object data by adding 2.5D graphics in the comp. The terrain was created using a mixture of X-Particles, lots of splines and a fair amount of 2.5D graphic elements." To depict a surge in mobile phone usage, a bar graph was made using MoGraph, and which appears beneath the terrain map.

"Cinema 4D was great when modeling within a set of design rules – which I find a great approach for this type of UI work," says Hill. "This made things easier when needing to keep the overall styling of multiple animations within a single body of work."

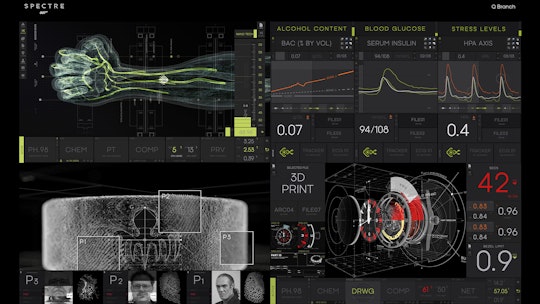

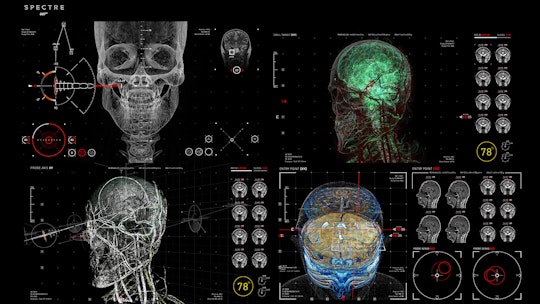

For the X-ray skull screens, Hill modeled many different layers, including bone, veins, arteries, nerves and sections of the brain. He then rendered out multiple passes of the different layers for compositing in After Effects. "This gave me excellent flexibility when creating the final treatment and isolating various parts of the skull," he comments. "The needles were created using a mixture of 3D and 2D elements and composited separately over the main 3D skull. A lot of rendering!"

Among the wide variety of subject matter, Hill admits that the medical organic content was among the most challenging. "We used a mixture of displacement maps and Fresnel shaders with various layered noise shaders to create the organic electron-microscopic look," he explains. "Using displacement maps as a slightly ad-hoc approach for modelling is a great way to create organic surfaces, and are quick to work with."

"For us, Cinema 4D is one of the quickest, most intuitive and creative tools around. You can do pretty much everything within a single application. MoGraph and Hair are fantastic modules and a great strength. Network rendering is easy to set up and reliable as well as easy to monitor. It's also very stable."

All images courtesy of Vincent London.

Vincent London Website:

www.vincentlondon.com